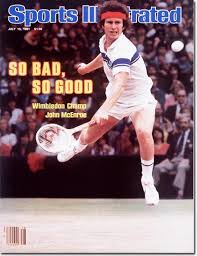

You know, having a conversation is a lot like playing tennis. A statement is made from one person to another, then it's responded to, tossed around, back and forth, each person trying to make his or her "point", each trying to "score". This can be obvious, as in a debate, or it can be subtle, as in a friendly dialogue. To some people, even saying "hello" can be an attempt at making a score before your opponent does. That's how it was in the evening of March 13, 1984, when I looked in my rearview mirror and found that John McEnroe was sitting in the back seat of my cab.

It was the doorman of his high-rise on East End Avenue who'd hailed me and opened the door for him but since I'd been looking down at my trip sheet, filling in the required information, I hadn't yet noticed who my new passenger was. I simply called out my usual "hello" and awaited the response. Would this one be friendly, in a big rush, arrogant, a drunk, a serial killer, or what? McEnroe's response was a hard, direct shot, you might say, to my forehand.

"The Garden," he said.

Now, what was most important here was what wasn't said. He didn't say "hello" back to me. He didn't say "please". He didn't say "Madison Square". Just "the Garden", as if I automatically knew who he was and which garden he was talking about. It was more of an order than a request and at the same time it tested the ability of the recipient (me) to respond in kind. An excellent opening -- I didn't yet know who he was, but he'd already scored. Point, McEnroe.

I looked straight into the rearview mirror, wondering who would be speaking to me this way. I recognized him immediately and shot back my own gut response:

"McEnroe," I blurted out, showing surprise but no great enthusiasm.

I give myself a point here because: a) I returned his sharp opening with one of my own. If he had intended to be blunt with no mincing of words, he got the same from me. b) I didn't show any false respect or false adulation or false friendliness. It was just "McEnroe", not "Mr. McEnroe", or "Oh, John McEnroe!" Basically I was conveying an attitude that said, Okay, I know who you are, but you're not on a tennis court, buddy, you're sitting in my cab, so don't start up with any of those shenanigans you're famous for. I can hit your serve. Point, Salomon.

His return caught me off guard. "Yes, it's me," he said, more to himself than to me and barely loud enough to be heard.

Now this was a switch, a complete change of style. His words could be interpreted as "Yes, the Great One is in your presence," but his tone was self-deprecating. Here was John McEnroe in person poking fun at John McEnroe the celebrity, actually satirizing himself. It was an impressive display of flexibility as a conversationalist. Point, McEnroe.

We volleyed as we headed south on East End Avenue.

"Are you playing tonight?" I asked, thinking maybe there was a tennis match at the Garden. No, he said, he was going to a Knicks game.

"Take the Drive?" I asked. (Meaning the FDR Drive, the highway that runs along the east side of Manhattan.)

"Yeah, please."

"Who are the Knicks playing tonight?"

"The Suns."

A couple more easy lobs were exchanged with no points scored.

Then, fearing the conversation might peter out for lack of fuel, I changed tempo by employing a technique I've used on other celebrities. I express my regrets that I'm not all that familiar with their area of expertise (even if I am) because here would be a great opportunity for me to learn something from someone so renown in that field. Celebrities live lives of annoyance from mundane questions posed by strangers and this may cause them to be reluctant to engage. So by pleading ignorance (or even pretending you don't recognize them) it has the effect of putting them at ease.

"Too bad I don't really know that much about tennis," I kind-of-lied as I made a left on 79th Street and approached the entrance to the Drive, "or I might be able to hold down an intelligent conversation here. I mean, I play a little, but I don't really know the fine points of the game."

Looking in the mirror, I watched his facial expression loosen up just a notch. I edged into the opening I had created. "Funny," I said, "I seem to keep getting professional tennis players in my cab."

McEnroe was interested. "Really? Who?"

I could feel a big score coming up. Here was the famous John McEnroe showing an interest in the not-famous me. To hell with modesty, a surge of what let's call self-importance was rising from within and it felt good.

I told him about a couple of fares I'd had with tennis players whose names I didn't remember. After talking for half a minute, however, I realized I was getting too chatty and that McEnroe's interest was waning. So I served him up my big story ("What It Takes, Part 1") about how the previous summer I'd driven Mike Estep, Martina Navratilova's coach, out to a private club in Queens to practice with her; how Mike was such a great guy; how he'd asked me if I'd like to watch them practice; how I'd always wondered if I could return the serve of a pro, so I asked Mike if he'd hit me a few balls when we got there; and how -- isn't this great? -- he did.

McEnroe was all ears. Not to brag but, really, I had the guy in the palm of my hand.

"Could you hit it?" he asked.

John McEnroe, the number one tennis player in the world, wants to know about my tennis game. Yes! Point, Salomon!

"Yeah," I said and, not trying to disguise my pride, I told him how I'd actually been able to get my racquet -- actually, Martina's racquet, ha-ha -- on the ball. Not with any authority, mind you, but still, after a few serves I was getting my timing down and I could hit it. Not bad for an amateur, huh?

McEnroe moved forward, a concerned look on his face.

"Who was that again?"

"Mike Estep," said I.

"Oh," he said, and he moved comfortably back in his seat again. "Well, you know, Mike's never been known for his serve."

Ping!

The little bubble I'd been sitting in for the last seven months came bursting apart and evaporated into the atmosphere.

"Mike's never been known for his serve."

With one quick stroke I'd been reduced to the pathetic little tennis wannabe I actually was.

Point, set, match -- McEnroe.

It was the doorman of his high-rise on East End Avenue who'd hailed me and opened the door for him but since I'd been looking down at my trip sheet, filling in the required information, I hadn't yet noticed who my new passenger was. I simply called out my usual "hello" and awaited the response. Would this one be friendly, in a big rush, arrogant, a drunk, a serial killer, or what? McEnroe's response was a hard, direct shot, you might say, to my forehand.

"The Garden," he said.

Now, what was most important here was what wasn't said. He didn't say "hello" back to me. He didn't say "please". He didn't say "Madison Square". Just "the Garden", as if I automatically knew who he was and which garden he was talking about. It was more of an order than a request and at the same time it tested the ability of the recipient (me) to respond in kind. An excellent opening -- I didn't yet know who he was, but he'd already scored. Point, McEnroe.

I looked straight into the rearview mirror, wondering who would be speaking to me this way. I recognized him immediately and shot back my own gut response:

"McEnroe," I blurted out, showing surprise but no great enthusiasm.

I give myself a point here because: a) I returned his sharp opening with one of my own. If he had intended to be blunt with no mincing of words, he got the same from me. b) I didn't show any false respect or false adulation or false friendliness. It was just "McEnroe", not "Mr. McEnroe", or "Oh, John McEnroe!" Basically I was conveying an attitude that said, Okay, I know who you are, but you're not on a tennis court, buddy, you're sitting in my cab, so don't start up with any of those shenanigans you're famous for. I can hit your serve. Point, Salomon.

His return caught me off guard. "Yes, it's me," he said, more to himself than to me and barely loud enough to be heard.

Now this was a switch, a complete change of style. His words could be interpreted as "Yes, the Great One is in your presence," but his tone was self-deprecating. Here was John McEnroe in person poking fun at John McEnroe the celebrity, actually satirizing himself. It was an impressive display of flexibility as a conversationalist. Point, McEnroe.

We volleyed as we headed south on East End Avenue.

"Are you playing tonight?" I asked, thinking maybe there was a tennis match at the Garden. No, he said, he was going to a Knicks game.

"Take the Drive?" I asked. (Meaning the FDR Drive, the highway that runs along the east side of Manhattan.)

"Yeah, please."

"Who are the Knicks playing tonight?"

"The Suns."

A couple more easy lobs were exchanged with no points scored.

Then, fearing the conversation might peter out for lack of fuel, I changed tempo by employing a technique I've used on other celebrities. I express my regrets that I'm not all that familiar with their area of expertise (even if I am) because here would be a great opportunity for me to learn something from someone so renown in that field. Celebrities live lives of annoyance from mundane questions posed by strangers and this may cause them to be reluctant to engage. So by pleading ignorance (or even pretending you don't recognize them) it has the effect of putting them at ease.

"Too bad I don't really know that much about tennis," I kind-of-lied as I made a left on 79th Street and approached the entrance to the Drive, "or I might be able to hold down an intelligent conversation here. I mean, I play a little, but I don't really know the fine points of the game."

Looking in the mirror, I watched his facial expression loosen up just a notch. I edged into the opening I had created. "Funny," I said, "I seem to keep getting professional tennis players in my cab."

McEnroe was interested. "Really? Who?"

I could feel a big score coming up. Here was the famous John McEnroe showing an interest in the not-famous me. To hell with modesty, a surge of what let's call self-importance was rising from within and it felt good.

I told him about a couple of fares I'd had with tennis players whose names I didn't remember. After talking for half a minute, however, I realized I was getting too chatty and that McEnroe's interest was waning. So I served him up my big story ("What It Takes, Part 1") about how the previous summer I'd driven Mike Estep, Martina Navratilova's coach, out to a private club in Queens to practice with her; how Mike was such a great guy; how he'd asked me if I'd like to watch them practice; how I'd always wondered if I could return the serve of a pro, so I asked Mike if he'd hit me a few balls when we got there; and how -- isn't this great? -- he did.

McEnroe was all ears. Not to brag but, really, I had the guy in the palm of my hand.

"Could you hit it?" he asked.

John McEnroe, the number one tennis player in the world, wants to know about my tennis game. Yes! Point, Salomon!

"Yeah," I said and, not trying to disguise my pride, I told him how I'd actually been able to get my racquet -- actually, Martina's racquet, ha-ha -- on the ball. Not with any authority, mind you, but still, after a few serves I was getting my timing down and I could hit it. Not bad for an amateur, huh?

McEnroe moved forward, a concerned look on his face.

"Who was that again?"

"Mike Estep," said I.

"Oh," he said, and he moved comfortably back in his seat again. "Well, you know, Mike's never been known for his serve."

Ping!

The little bubble I'd been sitting in for the last seven months came bursting apart and evaporated into the atmosphere.

"Mike's never been known for his serve."

With one quick stroke I'd been reduced to the pathetic little tennis wannabe I actually was.

Point, set, match -- McEnroe.

Damn!

I made a right and got on the FDR Drive. Having been so profoundly reduced in stature, I found I could think of nothing to say to McEnroe so I just reverted to my job description as a New York City taxi driver and stepped on the gas. Soon we were barreling along at 50 miles per hour in the middle lane, and for the next half a minute there continued to be no conversation between us, McEnroe no doubt quietly savoring the conquest of my dignity. Understandably my mood began taking a turn toward the Dark Side. What good was living, anyway? There's always some venomous creature waiting to put its fangs into you just when life seems all zippity-do-dah. Why continue slogging on with it?

I made a right and got on the FDR Drive. Having been so profoundly reduced in stature, I found I could think of nothing to say to McEnroe so I just reverted to my job description as a New York City taxi driver and stepped on the gas. Soon we were barreling along at 50 miles per hour in the middle lane, and for the next half a minute there continued to be no conversation between us, McEnroe no doubt quietly savoring the conquest of my dignity. Understandably my mood began taking a turn toward the Dark Side. What good was living, anyway? There's always some venomous creature waiting to put its fangs into you just when life seems all zippity-do-dah. Why continue slogging on with it?

The idea of an end-it-all-with-a-glorious-bang entered my mind. I could unfasten my seat belt, pick up speed to about 100 miles per hour, and crash into the stone wall that runs alongside the highway. McEnroe hadn't fastened his own seat belt so he'd probably go flying into the East River. This concept had an element of poetic justice to it which I found very appealing. Mike's never been known for his serve, huh? We'll see about that. I moved the cab over into the right lane and started looking for a good place in the wall to crash the cab.

But then, wait. I reconsidered.

All right, one way of looking at it would be that I had been demolished, even humiliated, by McEnroe. But let's take a step back and delve into this a bit, shall we? Here's a guy who is ranked NUMBER ONE in the WORLD. There are MILLIONS of tennis players, ALL OVER THE WORLD. They play this sport in schools, in colleges, in leagues, in private clubs, or just with friends. If you're GREAT at it you may actually become a professional and make some kind of a living at it. But then you're up against all the other players from ALL OVER THE WORLD who are also GREAT. Nevertheless you may become an elite player, rise high in the rankings, and become famous, respected, and wealthy. But if you're the GREATEST OF THE GREAT -- if you are ranked NUMBER ONE IN THE WORLD -- you will have earned the AWE of both the general public and your own colleagues because NO ONE IN THE WORLD CAN BEAT YOU! NO ONE!

And yet John McEnroe, the best tennis player in the world, and, some might say, the best tennis player of all time, is concerned that maybe his taxi driver can hit his serve. But then, oh, it's okay. It was only Mike Estep. I'm safe.

Ladies and gentlemen, what we're looking at here is compulsive competitiveness of asylum magnitude and I suppose we're also looking at what it takes to be Number One in tennis and some other sports. He is surrounded by assassins. Everyone is a threat. This is a guy who is one referee's bad call away from being surrounded by men in white coats and whisked off to the happy farm.

No, I decided, I would not crash the cab into the stone wall that runs alongside the FDR Drive. In an act of considerable magnanimity, I would let McEnroe live. I realized he hadn't won the match, he'd only won a set. So the game was still on. But what I needed to do here was to clarify for myself what the object of the game we were playing actually was.

But then, wait. I reconsidered.

All right, one way of looking at it would be that I had been demolished, even humiliated, by McEnroe. But let's take a step back and delve into this a bit, shall we? Here's a guy who is ranked NUMBER ONE in the WORLD. There are MILLIONS of tennis players, ALL OVER THE WORLD. They play this sport in schools, in colleges, in leagues, in private clubs, or just with friends. If you're GREAT at it you may actually become a professional and make some kind of a living at it. But then you're up against all the other players from ALL OVER THE WORLD who are also GREAT. Nevertheless you may become an elite player, rise high in the rankings, and become famous, respected, and wealthy. But if you're the GREATEST OF THE GREAT -- if you are ranked NUMBER ONE IN THE WORLD -- you will have earned the AWE of both the general public and your own colleagues because NO ONE IN THE WORLD CAN BEAT YOU! NO ONE!

And yet John McEnroe, the best tennis player in the world, and, some might say, the best tennis player of all time, is concerned that maybe his taxi driver can hit his serve. But then, oh, it's okay. It was only Mike Estep. I'm safe.

Ladies and gentlemen, what we're looking at here is compulsive competitiveness of asylum magnitude and I suppose we're also looking at what it takes to be Number One in tennis and some other sports. He is surrounded by assassins. Everyone is a threat. This is a guy who is one referee's bad call away from being surrounded by men in white coats and whisked off to the happy farm.

No, I decided, I would not crash the cab into the stone wall that runs alongside the FDR Drive. In an act of considerable magnanimity, I would let McEnroe live. I realized he hadn't won the match, he'd only won a set. So the game was still on. But what I needed to do here was to clarify for myself what the object of the game we were playing actually was.

I thought about it. For him, I realized, it was to shape me into a dutiful listener so he could hear himself pontificate. But for me, the game, in the time-honored tradition of taxi-driving, was to set my passenger up for giving me a big tip.

I awarded myself a point for this brilliant insight and the match continued.

Easing up on the pedal, I steered the cab back into the center lane. Our conversation resumed, turning to sports in general -- football, baseball, hockey, basketball. I began to notice that he'd listen carefully to whatever I had to say, wait just a moment, and then correct me. My strategy was to listen carefully to him as well, but not to correct him. For example, when at one point he interjected into the conversation that tennis is the greatest sport that ever was, I didn't contradict him even though everybody knows that baseball is the greatest sport that ever was. Agreement creates affinity and affinity is crucial in the tipping phase of the ride. So it could have appeared to an observer that McEnroe was scoring all the points here, but in reality I was holding even with him.

We exited the FDR at 34th Street. The conversation had turned to boxing and McEnroe was telling me that Larry Holmes, who was then the undefeated heavyweight champion, would soon lose.

"Who'll beat him?" I asked.

"He'll beat himself," McEnroe snapped back. A return with some real zing to it, especially considering that the person giving it was himself was the champion of the tennis world at that time, and McEnroe received a point for style.

We moved along on 34th Street and as we approached 2nd Avenue McEnroe committed a breach of taxicab etiquette by telling me to turn left and take 31st Street to the Garden. The offense here is giving simple directions to a professional driver, as if I don't know how to get to Madison Square Garden. But in this case I let the faux pas pass without comment as it suited my game plan. The street he chose is actually the slowest way to get to the Garden from the East Side because you'll get a red light at every intersection. He was adding three minutes to the ride. That's good for the meter but what I liked most was that it was giving me more time to work him for the tip. Advantage, Salomon.

As we began our crosstown trek on 31st Street McEnroe, perhaps realizing that the end of the ride was approaching, suddenly seized complete control of the conversation and began to preach in earnest about his issues with tennis. This was good news. I could be getting taxi-driver-as-therapist money here.

First he hit on the officiating. His complaint, he said, was that the officials aren't professional officials. He pointed out that in baseball and football the players get to know the officials on a first-name basis. In a close call their decisions are respected because the players know they are competent. But in tennis, he said, you see new faces in every tournament, officials you've never met before. Trust in their competence isn't given a chance to develop.

I awarded myself a point for this brilliant insight and the match continued.

Easing up on the pedal, I steered the cab back into the center lane. Our conversation resumed, turning to sports in general -- football, baseball, hockey, basketball. I began to notice that he'd listen carefully to whatever I had to say, wait just a moment, and then correct me. My strategy was to listen carefully to him as well, but not to correct him. For example, when at one point he interjected into the conversation that tennis is the greatest sport that ever was, I didn't contradict him even though everybody knows that baseball is the greatest sport that ever was. Agreement creates affinity and affinity is crucial in the tipping phase of the ride. So it could have appeared to an observer that McEnroe was scoring all the points here, but in reality I was holding even with him.

We exited the FDR at 34th Street. The conversation had turned to boxing and McEnroe was telling me that Larry Holmes, who was then the undefeated heavyweight champion, would soon lose.

"Who'll beat him?" I asked.

"He'll beat himself," McEnroe snapped back. A return with some real zing to it, especially considering that the person giving it was himself was the champion of the tennis world at that time, and McEnroe received a point for style.

We moved along on 34th Street and as we approached 2nd Avenue McEnroe committed a breach of taxicab etiquette by telling me to turn left and take 31st Street to the Garden. The offense here is giving simple directions to a professional driver, as if I don't know how to get to Madison Square Garden. But in this case I let the faux pas pass without comment as it suited my game plan. The street he chose is actually the slowest way to get to the Garden from the East Side because you'll get a red light at every intersection. He was adding three minutes to the ride. That's good for the meter but what I liked most was that it was giving me more time to work him for the tip. Advantage, Salomon.

As we began our crosstown trek on 31st Street McEnroe, perhaps realizing that the end of the ride was approaching, suddenly seized complete control of the conversation and began to preach in earnest about his issues with tennis. This was good news. I could be getting taxi-driver-as-therapist money here.

First he hit on the officiating. His complaint, he said, was that the officials aren't professional officials. He pointed out that in baseball and football the players get to know the officials on a first-name basis. In a close call their decisions are respected because the players know they are competent. But in tennis, he said, you see new faces in every tournament, officials you've never met before. Trust in their competence isn't given a chance to develop.

I thought, wow, you know, he makes a good point here, and I awarded him one. I'd never heard that argument expressed before and it made perfect sense -- of course, a lack of trust in the professionalism of the officials would create problems with the players. But a few moments later I realized, wait, this is McEnroe's justification for why it's okay to berate officials during a match, as he was so famous for doing. I took the point away for faking himself out.

Next, he took on the fans. "New York fans are the worst," he squawked, recalling when he'd played against Vitas Gerulaitis, who was from Queens, in the finals of the U.S. Open in 1979. What are the odds, he asked, of two guys who are both from Queens ever making it to the finals of the U.S. Open, played in Queens, in the same year? And the fans?

"They booed both of us!"

Now here McEnroe was clearly committing a foul. It would be one thing if he had it out for one particular fan or for even a certain type of fan. But all New York fans? Come on. I had no choice but to deduct a point for unsportsmanlike conduct.

We arrived at the Garden. I pulled up to a special side entrance on 31st Street where McEnroe wanted to be dropped off, stopped the cab, and started tallying up the points. With the penalty point deducted from his score it appeared to be a dead heat. So... this match was going to be decided by the tip. The fare on the meter was $5.20. (This was in 1984. Today that ride would cost around $15.) A cheap or -- considering it's a celebrity -- even an average tip would force me to conclude that my efforts had been in vain and I would have to concede the match to my opponent. It would have to be a definitive, excessively generous gratuity to win.

With tension mounting, McEnroe opened his door and stepped out onto the street. He reached into the pocket of his coat and, stepping halfway back into the cab, handed me two bills: a five and a single. It was going to be an eighty-cent tip, slightly less than average for a $5.20 fare. I would have to interpret this as a snub, a cheapskate's ace, and give the final point and the match to McEnroe.

But wait!

McEnroe reached into his pocket again. Out came several more bills which he handed to me with an almost apologetic look on his face. He closed the door, waved goodbye, and walked toward the Garden, smiling. I counted the bills. There were six singles. So McEnroe had tipped me $6.80 on a $5.20 fare, better than double the meter. It was the best tip I'd ever received from a celebrity, a record that stood for twelve years.

Point, set, match -- Salomon!

********

Notes:

1. This is the second in a three-part series, "What It Takes". Stay tuned for Part 3, "McEnroe Returns".

2. I am able to recall the details of a ride taken 34 years ago is because a) it was particularly memorable, and b) I've always kept journals of my most interesting rides.

3. There's a documentary recently released about McEnroe's year, 1984 (the same year he was in my cab), in which he won an incredible 82 out of 85 matches. To see a clip from In The Realm Of Perfection click below:

4. Click on this one to see a taxi nearly running over McEnroe (from the movie Mr. Deeds):